Introduction

December 2016 / Matthew F. Rech / School of Geography, Politics and Sociology, Newcastle University - On 8 January 2002 in the US, George Bush Jr. signed into law an educational federal grant Act entitled ‘ No Child Left Behind ’ Though seemingly commendable at first glance, it being designed to improve academic attainment in disadvantaged state- funded schools (Zgonjanin 2006 ), a closer look at NCLBAs 670 pages revealed a provision that allowed military recruiters near unimpeded access to the personal information of enrolled students. On pain of forfeiture of federal funding, schools covered by the Act were required to release student names, addresses and telephone numbers to military recruiters. As Nava ( 2011 , 465) details, although

December 2016 / Matthew F. Rech / School of Geography, Politics and Sociology, Newcastle University - On 8 January 2002 in the US, George Bush Jr. signed into law an educational federal grant Act entitled ‘ No Child Left Behind ’ Though seemingly commendable at first glance, it being designed to improve academic attainment in disadvantaged state- funded schools (Zgonjanin 2006 ), a closer look at NCLBAs 670 pages revealed a provision that allowed military recruiters near unimpeded access to the personal information of enrolled students. On pain of forfeiture of federal funding, schools covered by the Act were required to release student names, addresses and telephone numbers to military recruiters. As Nava ( 2011 , 465) details, although

The provision gave parents the ability to ‘ opt-out ’ of releasing this information only if they first submit written notification to the school ... NCLBA ... does not provide any requirement, instruction, or mechanism to ensure that parents are aware of this.

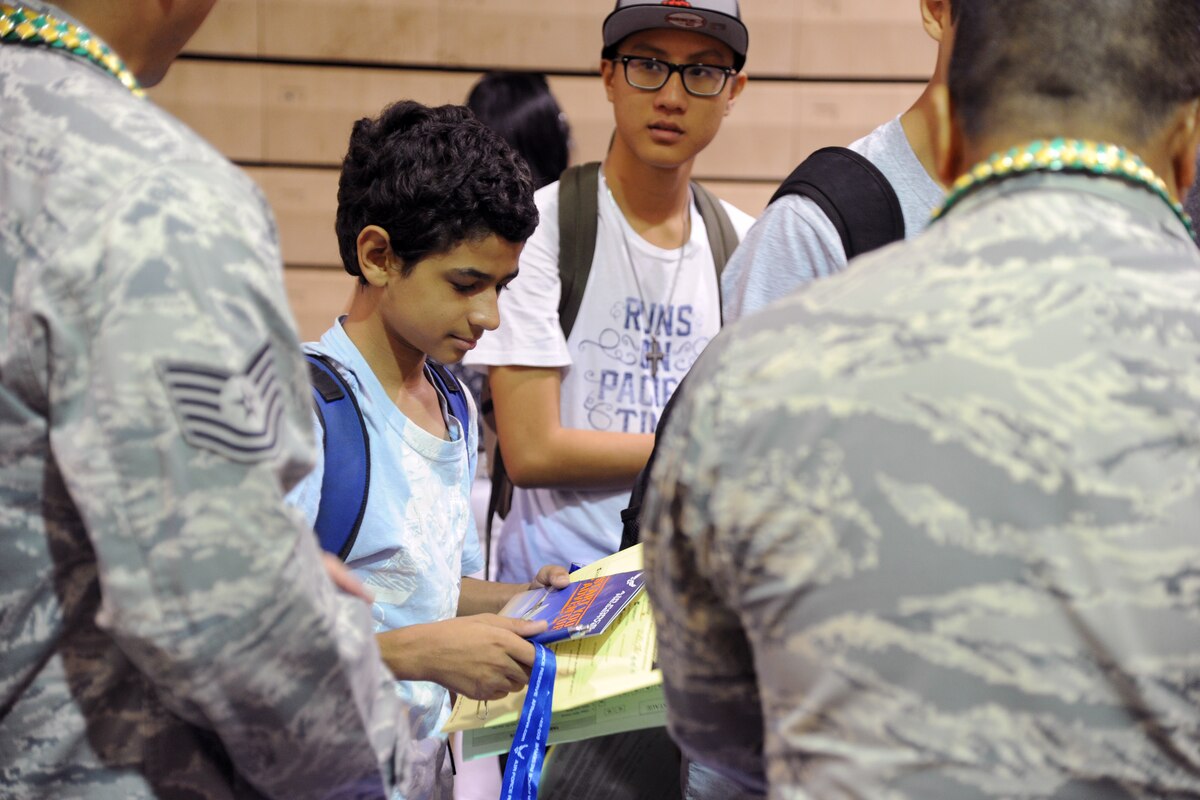

The data-gathering proposition in the NCLBA, just as with the Pentagon ’ s Joint Advertising Marketing and Research database (Ferner 2006 ), is designed, at root, to streamline the solicitations of military recruiters. It focuses a military recruiting and retention budget, which reached $7.7 billion in 2008 (Vogel 2009 ), effectively according to gender, age, ethnicity and recreational interests, amongst other variables. Combined with the access granted to military recruiters in that of ‘ extra-curricular ’ junior reserve Officer Training Corps programmes, or the Armed Services Aptitude Battery test (a ‘ Careers ’ test offered by two thirds of all US schools) (Allison and Solnit 2007 ), it is clear that military recruiting is an important set of practices in what Harding and Kershner ( 2011 ) call a ‘ deeply embedded ’ culture of militarism in the US.

Though cultures of militarism differ markedly between places, their being a symptom of nationalisms, political, geographical and historical imaginaries, and a product of the state ’ s apparatus of persuasion, militarism in the UK is also bound to legislative efforts to promote a ‘ military ethos ’ in schools. In July 2012, for instance, shadow secretaries Stephen Twigg (education) and Jim Murphy (defence) wrote to the Telegraph to outline their vision for the future involvement of the British Armed Forces in schools (Twigg and Murphy 2012 ), opining that:

We are all incredibly proud of the work our Armed Forces do in keeping us safe at home and abroad. They are central to our national character, just as they are to our national security. The ethos and values of the Services can be significant not just on the battlefield but across our society.

Practically, Twigg and Murphy called for the widening of military Cadet schemes; new schools with service specialisms; the use of military advisors and reservists for physical education and other curricula; and a rebalancing of military involvement particularly as it is absent from the majority of state schools. The military might be best-placed to teach, they suggest, a ‘ service ethos ’ , a sense of ‘ responsibility and comradeship, and ‘ the value of hard work ’ and ‘ public service ’ .

Twigg and Murphy ’ s vision, has, since November 2012, variously become a reality with an expansion of the Cadets, a ‘ Troops to Teachers ’ programme, and Government support for fledgling military ‘ free-schools ’ and academies (Education.gov.uk 2014 ). Much like critics of NCLBA however, there are some who can ’ t help but see the connection between the Department for Education ’ s ‘ Ethos ’ programme and military recruitment. Indeed, as Sangster ( 2012 ) notes, along with the fact that the DfE does not provide an examination of what ‘ military ethos ’ actually means, or why schools are the best place to teach hierarchy, demand for obedience, or the value of the use of force, there are clear, and clearly troubling, links between the integration of military attitudes into the structure of national education policy and eventual enlistment (Armstrong 2007 ; Lutz and Bartlett 1995 ).

June 22, 2022 / Alex Skopic / Current Affairs - Today’s conservatives, to hear them tell it, are deeply concerned with the safety of children in schools. After all, anything from a gender-neutral toilet, which could invite sexual predators, to a Toni Morrison novel, which might cause a reader “discomfort” about their race, could be lurking. One has to be vigilant. So you might assume that if a group of specially-trained adults started hanging around schools, trying to lure minors into dangerous situations under false pretenses, the political Right would be up in arms about it, demanding an influx of police and private security guards to deal with the menace. Unless, of course, these duplicitous strangers are with the military—and then, somehow, the impulse to ‘think of the children’ disappears.

June 22, 2022 / Alex Skopic / Current Affairs - Today’s conservatives, to hear them tell it, are deeply concerned with the safety of children in schools. After all, anything from a gender-neutral toilet, which could invite sexual predators, to a Toni Morrison novel, which might cause a reader “discomfort” about their race, could be lurking. One has to be vigilant. So you might assume that if a group of specially-trained adults started hanging around schools, trying to lure minors into dangerous situations under false pretenses, the political Right would be up in arms about it, demanding an influx of police and private security guards to deal with the menace. Unless, of course, these duplicitous strangers are with the military—and then, somehow, the impulse to ‘think of the children’ disappears.

May 18, 2022 / Melissa Chan /

May 18, 2022 / Melissa Chan /  May 16, 2022

May 16, 2022 April 18th, 2022 / Roberto Camacho /

April 18th, 2022 / Roberto Camacho /  December 2016 / Matthew F. Rech / School of Geography, Politics and Sociology, Newcastle University - On 8 January 2002 in the US, George Bush Jr. signed into law an educational federal grant Act entitled ‘ No Child Left Behind ’ Though seemingly commendable at first glance, it being designed to improve academic attainment in disadvantaged state- funded schools (Zgonjanin 2006 ), a closer look at NCLBAs 670 pages revealed a provision that allowed military recruiters near unimpeded access to the personal information of enrolled students. On pain of forfeiture of federal funding, schools covered by the Act were required to release student names, addresses and telephone numbers to military recruiters. As Nava ( 2011 , 465) details, although

December 2016 / Matthew F. Rech / School of Geography, Politics and Sociology, Newcastle University - On 8 January 2002 in the US, George Bush Jr. signed into law an educational federal grant Act entitled ‘ No Child Left Behind ’ Though seemingly commendable at first glance, it being designed to improve academic attainment in disadvantaged state- funded schools (Zgonjanin 2006 ), a closer look at NCLBAs 670 pages revealed a provision that allowed military recruiters near unimpeded access to the personal information of enrolled students. On pain of forfeiture of federal funding, schools covered by the Act were required to release student names, addresses and telephone numbers to military recruiters. As Nava ( 2011 , 465) details, although